DARFUR REPORT 2: UNAMID withdraws, key issues and proposed solutions

Summary

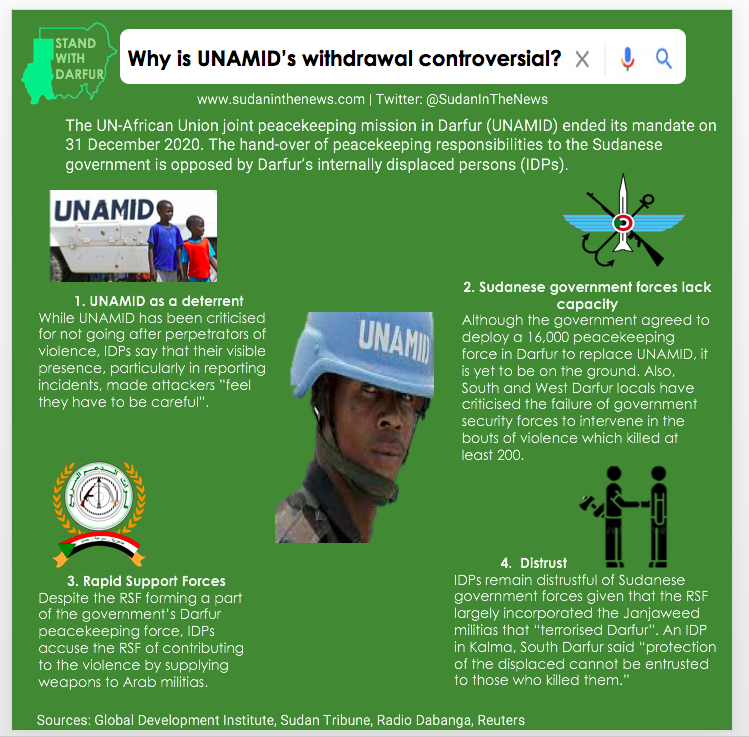

The joint UN-African Union peacekeeping mission in Darfur (UNAMID) ended its mandate on 31 December 2020, despite protests from Darfur’s internally displaced persons (IDPs). Less than three weeks after UNAMID’s withdrawal, South and West Darfur were rocked by deadly tribal clashes that killed at least 200. In West Darfur’s al-Geneina, at least 159 were killed and over 90,000 were forced to flee their homes in a massacre triggered by a Masalit tribesman killing an Arab herder. In al-Gereida locality of South Darfur, clashes between the Arab-identifying Rizeigat tribe and the Fallata, who trace their origins to west Africa, killed over 40. This report identifies seven key issues contributing to insecurity in Darfur.

1. Darfur’s pre-existing legacy of conflict.

2. Isolated incidents between two people rapidly mushroom into violent episodes that kill swathes.

3. To compound matters, UNAMID’s withdrawal is viewed as premature given the increasing levels of intercommunal conflict in Darfur.

4. In addition, UNAMID provided reassurance to Darfur’s IDPs, despite being viewed as “imperfect”.

5. The Sudanese government is now tasked with peacekeeping responsibilities despite question marks over security forces capacity to maintain security.

6. Darfuri mistrust towards government forces lingers from the Darfur War.

7. The distrust is further intensified given that the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) are tasked with protecting Darfur despite their connection to Janjaweed militias that “terrorised” the region.

The proposed solutions for security in Darfur include: disarming militias, transitional justice, security and legal reforms, a new civilian protection mandate and a reversal of UNAMID’s withdrawal.

Events

A timeline of key events - please read the full briefing for more detail on specific events.

14 December - A sit-in in Kalma camp near Nyala, South Darfur, entered its second week, where protesters demanded that UNAMID is not withdrawn at the end of 2020. Similar protested occurred in IDP camps in Kabkabiya in North Darfur (Radio Dabanga, 14 December).

26 December - Internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Darfur have called for more sit-ins against the withdrawal of UNAMID before the achievement of comprehensive peace, security, disarmed militias, expelled settlers from IDP lands and the hand-over of war criminals to the International Criminal Court (Multiple sources, 26 December).

28 December - At least 15 tribesmen were killed and 34 were wounded during tribal clashes between Masalit farmers and Fallata herders in al-Gireda, South Darfur. The dispute began at a water well, before escalating into a firefight between the tribes in which two Fallata were shot dead. In retaliation, Fallata militants attacked Masalit neighbourhoods (Multiple sources, 28 December).

30 December – UNAMID (30 December) announced the end of its mandate, stating the drawdown will be undertaken in a phased manner across six months. The Sudanese government will “fully assume its primary role” in supporting the peace process, protecting civilians, including facilitation of delivery of humanitarian assistance and supporting the mediation of intercommunal conflicts.

7 January - Following the end of UNAMID’s mandate, its replacement mission, the United Nations Integrated Transition Assistance Mission in Sudan (UNITAMS), will be headed by German diplomat Volker Perthes, who will also be the Special Envoy of the UN Secretary General to Sudan (Multiple sources, 7 January).

18 January – Over 40 people were killed in clashes between the Fallata and Rizeigat tribes in Al-Tawil area of Gereida locality South Darfur. The Fallata, who trace their origins to the Fulani people of west Africa, and the Rizeigat, an Arab-identifying tribe, clash often over stolen livestock (Multiple sources, 18 January).

20 January - The death toll of the massacre in al-Geneina, West Darfur rose to 159, with over 90,000 fleeing their homes. The attacks were triggered by the killing of an Arab herdsman by a Masalit tribesman. Although the perpetrator was arrested, Arab militias took revenge (Radio Dabanga, 20 January).

20 January - Armed men opened fire trying to storm the residence of West Darfur Gov. Mohammed Abdalla al-Douma’s residence in the provincial capital of Geneina (AP, 20 January).

Seven key issues

1. Legacy of conflict

Darfur’s pre-existing legacy of war is further complicated by the rise in intercommunal violence which is exacerbated by the excess of weapons in the region and rivalries. Ahead of UNAMID ending its mandate on December 31, its Special Representative Jeremiah Mamabolo noted “major” challenges for security in Darfur including rising numbers of displaced people whenever conflict erupts, factional fighting between rebel groups, intercommunal conflicts and that the Sudan Liberation Movement of Abdelwahid al-Nur continuing to fight. While the major fighting in Darfur has stopped, sporadic intercommunal clashes in the region have increased in 2020, Mamabolo added (Radio Dabanga, 24 December). Indeed, Mohammed Osman, a Sudan researcher at Human Rights Watch (HRW), said HRW has documented an increase in intercommunal violence, exacerbated by the involvement of government forces (AP, 9 December).

Providing context on intercommunal conflict in Darfur, AFP (18 January) state that “decades of conflict have left the vast western region awash with weapons and divided by bitter rivalries,” despite the recent peace agreement. Key issues include land ownership and access to water, AFP add.

Following clashes that killed at least 159 in al-Geneina, West Darfur - Radio Dabanga (20 January) also provide context on the tensions between Rizeigat and Fallata herders, which “have a long history of fighting in South Darfur.” The Fallata are cattle herders from non-Arab ethnic origins. They race their roots to the Fulani of west Africa (AFP, 18 January). On the other hand, the Rizeigat are nomadic Arab herders who mainly herd cattle in South Darfur. When the Darfur War began in 2003, “many young Rizeigat herders were recruited to join the 'Janjaweed militia’”(Radio Dabanga, 20 January). As noted by Reuters (13 January) the RSF that are tasked with protecting Darfur “incorporated members of the Janjaweed militias that terrorised Darfuris.

2. Rapid mushrooming

The rapid mushrooming of the latest conflicts in South and West Darfur, from a market fistfight into violent interethnic episodes that killed over 200, “illustrates the persistent insecurity in Darfur as well as the folly of the Sudanese government’s premise that security in the region had improved sufficiently” for the peacekeepers to leave, said Jonas Horner of the International Crisis Group (New York Times, 20 January).

For example, the massacre in al-Geneina was reportedly triggered by the killing of an Arab herdsman by a member of the Masalit tribe. Although the perpetrator was arrested, the relatives of the victim sought revenge – culminating in large groups of armed men attacking al-Geneina and the two Kerending camps for the internally displaced “from all directions. According to the Darfur Bar Association (DBA), they were supported by groups of gunmen from North and Central Darfur and the border area with Chad (Radio Dabanga, 20 January). With regards to the clashes in South Darfur between the Fallata and Rizeigat, despite their aforementioned history of conflict, the most recent fatal episode was reportedly sparked by the killing of a shepherd (AP, 18 January).

3. UNAMID’s premature withdrawal

The withdrawal of UNAMID is considered concerning within the context of Darfur’s rising insecurity. Mohammed Osman, a Sudan researcher at Human Rights Watch, said the tribal violence in Darfur is an example of why many displaced people protested the end of UNAMID’s mandate (AP, 18 January). Indeed, Sheikh Ishag Abdallah, head of Kalma camp, told Radio Dabanga (26 December) that the withdrawal of UNAMID “is unacceptable in light of the current security situation”. He warned for further deterioration of the situation after the withdrawal of the UNAMID peacekeepers, and called for “alternative international protection if the mission will have to withdraw”. Similarly, Jan Egeland, secretary general of the Norwegian Refugee Council, warned that the security situation "could worsen" with peacekeepers "on their way out" (AFP, 18 January). According to Sudanese activist Nazek Awad, the risk of harm to Darfur is exacerbated by the absence of provisions for an independent party to monitor the situation on the ground after the exit of UNAMID. “The insecurity for displaced people will continue and increase,” she said (AP, 9 December).

The risks of UNAMID’s premature withdrawal have also been highlighted by various diplomats. Germany’s UN ambassador, Christoph Heusgen, cited the floods, poor harvest, COVID-19, reports of internal fights over control of gold mines, attacks against government forces, and low representation of women in transitional bodies to emphasise the risks of UNAMID’s withdrawal. Jose Singer, the Dominican Republic’s UN ambassador, said he was reminded of what happened in neighbouring Haiti after “the premature withdrawal” of UN peacekeepers, a reference to the ongoing insecurity in the country. Estonia’s UN ambassador, Sven Jurgenson, said “rushing the withdrawal risks losing the significant gains made by UNAMID over the years” (AP, 9 December). In addition, the symbolic presence of UNAMID also provided assurance to Darfuris.

4. UNAMID reassurance

Despite criticism of UNAMID’s failure to protect civilians, Darfuris have said its presence acts as a deterrent to militant attacks. Tanja Müller, a Professor of Political Sociology at the University of Manchester’s Global Development Institute (5 January), argues that the presence of UNAMID “did make a difference – even if not on the scale and scope hoped for or expected by those it aimed to protect.” Müller quotes a Darfuri refugee who said that while UNAMID “never went after the perpetrators” but “the UNAMID work of reporting incidents and coming to visit places where incidents have taken place made perpetrators feel that they have to be careful as their actions might be reported and they might be held responsible”.

Furthermore, Müller cites a 2016 academic report on UNAMID entitled ‘No One on the Earth Cares if We Survive, Except God and Sometimes UNAMID’ as a reflection of Darfuri beliefs that “UNAMID served as the only protection for the displaced, even if often imperfect”.

In a press release announcing their departure, UNAMID (30 December) said that the Sudanese government will “fully assume its primary role” in supporting the peace process, protecting civilians, including facilitation of delivery of humanitarian assistance and supporting the mediation of intercommunal conflicts. However, UNAMID’s withdrawal is compounded by the limited capacity of the Sudanese government in containing the violence in Darfur.

5. Government incapacity

Despite a belief that Sudan’s post-revolution government has a higher appetite for peace in Darfur, analysts have pointed to the failure to protect civilians during the recent attacks across Darfur that killed over 200. Furthermore, locals that witnessed the attacks have also pointed to the absence of government security forces.

According UNAMID’s former Special Representative Jeremiah Mamabolo, Sudan is now “in the right hands” for peacekeeping, in contrast to al-Bashir’s government which “would not allow UNAMID to dispense relief because it saw certain parts of Sudan as enemy territory” (Radio Dabanga, 24 December). Indeed, the Sudanese government has stressed its responsibility to protect and maintains security in Darfur following recent deadly intercommunal violent incidents in South and West Darfur that killed at least 200 (Sudan Tribune, 20 January).

However, following the clashes in al-Tawil Village in South Darfur between the Fallata and Rizeigat tribes that killed 56, Fallata spokesperson Ibrahim Mousa criticised the failure of government forces to intervene, despite the local army garrison being only five kilometres away from where the attack took place (Radio Dabanga, 20 January). Similarly, following the massacre in al-Geneina conducted by an Arab tribe, Masalit tribesman Saad Abdelrahman , expressed his surprise about the “complete absence of the army during the attacks” (Radio Dabanga, 19 January).

Thus, the violent incidents in South and West Darfur that killed over 200 led Jonas Horner, a Sudan analyst with the International Crisis Group, to conclude that: “the government comprehensively failed its first real test of maintaining security” (New York Times, 20 January).

Indeed, Sudan Tribune (17 January) note that while the government and armed groups agreed to deploy a 16,000 joint force in Darfur after the withdrawal of the UNAMID, it is yet to be on the ground. Columnist Shamael al-Nur said the continued civilian casualties in the region reflects the weak impact of the Juba peace agreement on the ground and the government’s failure to disarm the population. "Nothing makes the gunmen continue to shed blood more than their certitude that the law does not and will not affect them," she wrote. Moreover, not only are there doubts about the Sudanese government’s capacity to protect Darfuris, there is also mistrust among the population, particularly given the history of state-sponsored attacks on Darfur under the regime of Omar al-Bashir.

6. Mistrust

UNAMID’s Special Represenative Jeremiah Mamabolo cautioned that mistrust still runs deep and urged the transitional government in Khartoum to embark on the “huge task” of gaining the trust of the locals. Mamabolo said Darfuris “have been betrayed ... A lot of crimes and injustice have been committed against them, so they feel insecure” (AP, 9 December).

While “Darfuris say UNAMID offered a weak but necessary deterrent against militias originally armed by former president Omar al-Bashir to fight rebels,” community leader Sheikh Mousa Bahar Adam said IDPs are being “left with criminals” (Reuters, 13 January). Similarly, a leader of protests against UNAMID withdrawal in Kalma, South Darfur said “protection of the displaced cannot be entrusted to those who killed them” (Radio Dabanga,14 December). Such sentiments of distrust are partly caused by the protection of Darfur being entrusted to the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) militia.

7. RSF

With Sudan deploying a 20,000 peacekeeping force to Darfur, Reuters (13 January) note that IDPs in South Darfur “remain deeply distrustful” of government forces, particularly the RSF, “which incorporated members of the Janjaweed militias that terrorised Darfuris”. As recently as January 2021, RSF troops have reportedly conducted violence on Darfur. Al-Shafee’ Abdallah, coordinator of the camps for the displaced in Central Darfur, told Radio Dabanga (2 January) that RSF members burnt a pharmacy, looted 10 shops, and attacked workers at Zalingei Hospital in Central Darfur, with regular armed forces failing to intervene or stop the perpetrators (Radio Dabanga, 2 January). Similarly, Fallata spokesperson Ibrahim Mousa told Radio Dabanga (20 January) that he was surprised by the heavy weapons used during the militant attacks by Arab tribesmen in South Darfur, and alleged that RSF troops participated.

Furthermore, RSF seniority are also accused of being negligible in containing the violence. According to Adil Ali Yacoub, a resident of Gereda in South Darfur, intercommunal conflict between Fallata pastoralists and Masalit farmers were triggered by the RSF’s local head ignoring a directive to keep Fallata away from the area until a reconciliation conference took place (Ayin Network, 9 January).

Solutions

Disarmament

The Peace Support Committees Coordination organised a protest vigil in Khartoum against the ongoing violence in Darfur, submitting a memorandum which called for the

“the acceleration of the implementation of the Juba Peace Agreement, especially the security arrangements protocol, including the establishment of a disarmament mechanism” (Radio Dabanga, 28 December)

Transitional justice

A leader of a sit-in protest against UNAMID’s withdrawal demanded the restoration of lands traditionally used by a particular clan or tribal group, alongside individual and collective compensation for the displaced. The primary demands at the time of protest were that UNAMID remains until peace and security are secured, criminals are tried, settlers on the lands of the displaced are expelled, and militias are disarmed (Radio Dabanga, 14 December).

A new civilian protection mandate

The Darfur Women’s Action Group (DWAG, 8 January) call for the creation and enforcement of a civilian protection mandate that will last throughout the entirety of Sudan’s transitional period, alongside strong international presence with mechanisms for protection of human rights and verifiable measures to demonstrate progress across Sudan.

Security sector and legal reforms

Strategic Initiative for Women In The Horn of Africa (SIHA, 7 January) call for the government to launch a security sector reform taskforce that redefines the concepts of civilian protection and peacekeeping, including training of law enforcement personnel at all levels to ensure that rule of law is reflected on the ground. SIHA also suggest fundamental reforms of Sudan’s legal framework, including investment in rule of law institutions, alongside rewriting the “vague and conflicting” laws concerning sexual violence/abuse, and the reform of laws that provide impunity to military and paramilitary forces.

Reversing UNAMID’s decision

Columnist Osman al-Sayed calls for the UN and African Union to review the decision to withdraw UNAMID until weapons are collected from fugitives including militias and civilians and the return of the displaced and refugees to their villages until their causes of fear have disappeared (Al-Rakoba, 3 January).