#SudanUprising report: 3 major challenges facing the post-coup uprising in Sudan

After the coup: the uprising continues

Sudan’s situation is “very chaotic, because for the first time in Sudan’s history, we have both a coup and a revolution restarting,” with the current government being “a reflection of [former dictator Omar] al-Bashir’s regime”, says Kholood Khair, the managing partner at Insight Strategy Partners, a Khartoum-based think-tank. “The pro-democracy movement has a lot to fight for,” Khair added (East African, 16 April).

Although the pro-democracy movement continues fighting – the post-coup Sudan Uprising is fraught with challenges.

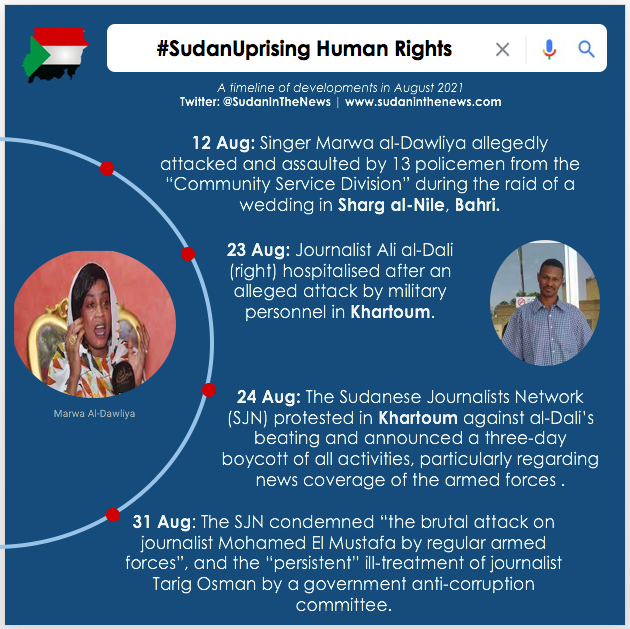

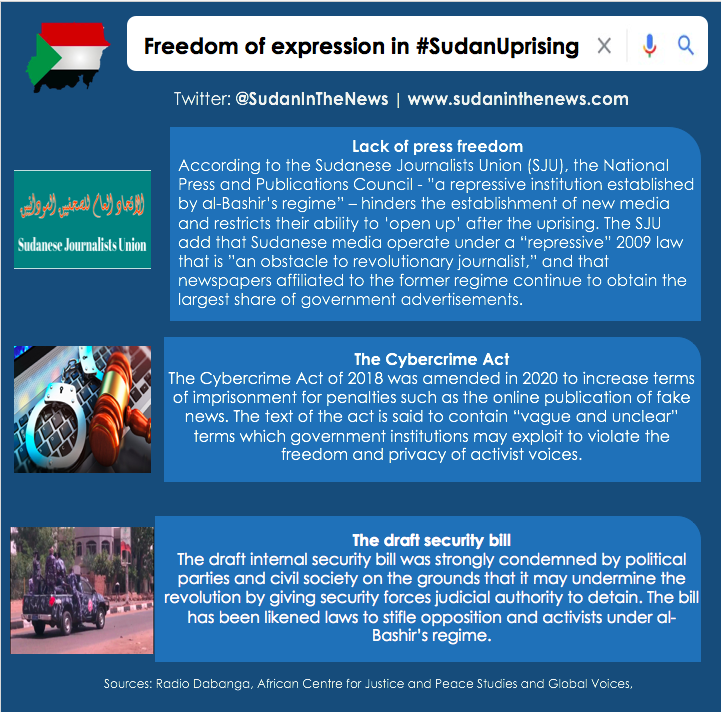

The first challenge that this report explores are the human rights infringements conducted by the coup regime led by Lt. Gen. Abdulfattah al-Burhan – the commander-in-chief of the Sudanese Armed Forces. Since taking power in a military coup on 25 October 2021, the regime has led a suppression of freedom of expression and press via brutal crackdowns on peaceful protesters and controlling and intimidating the media.

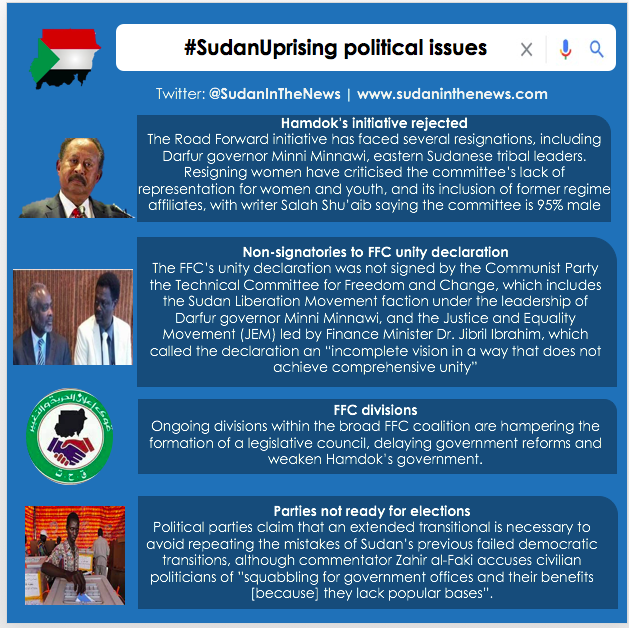

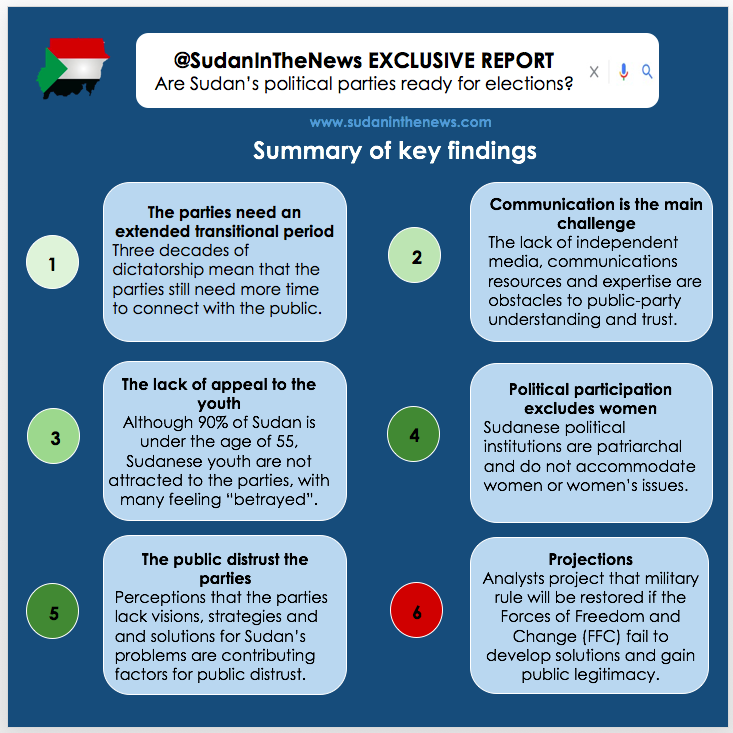

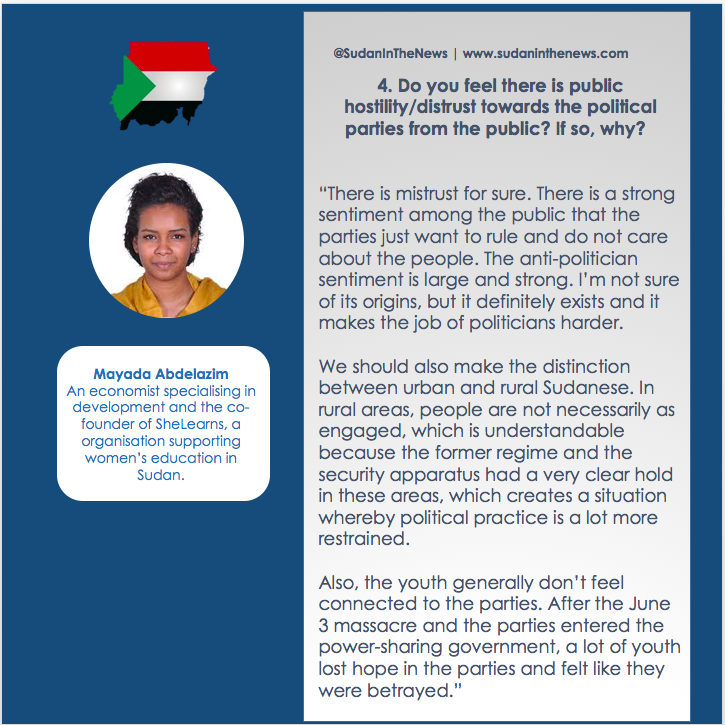

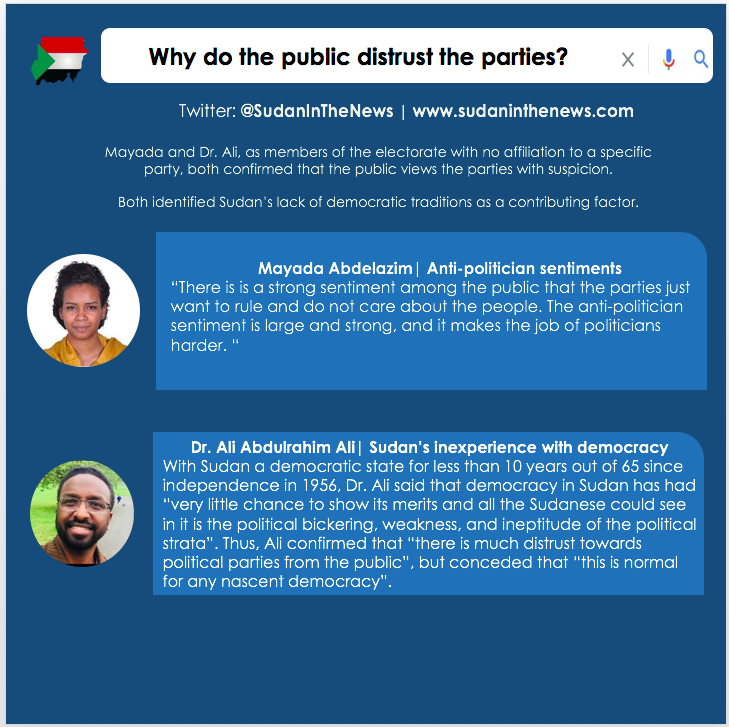

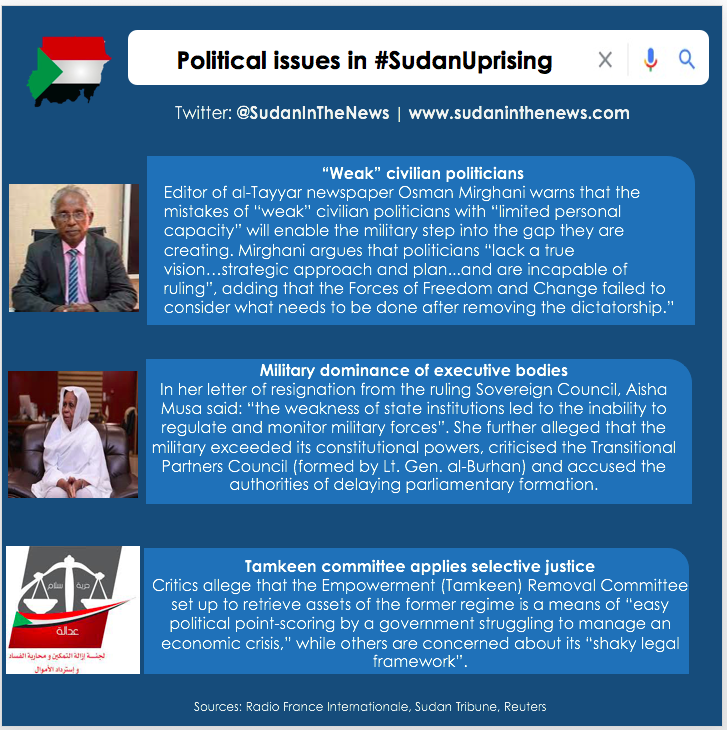

The second challenge the report examines are issues facing the pro-democracy movement. Firstly, the mistrust between the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) coalition of political parties that formed the civilian component of the pre-coup transitional government and the Resistance Committees who are the centre of revolutionary mobilisation help enable a military that exploits civilian divisions to justify their rule. Secondly, despite circumventing their exclusion from the state media by publishing charters on social media, analysts debate whether the Resistance Committees can implement a roadmap to democracy.

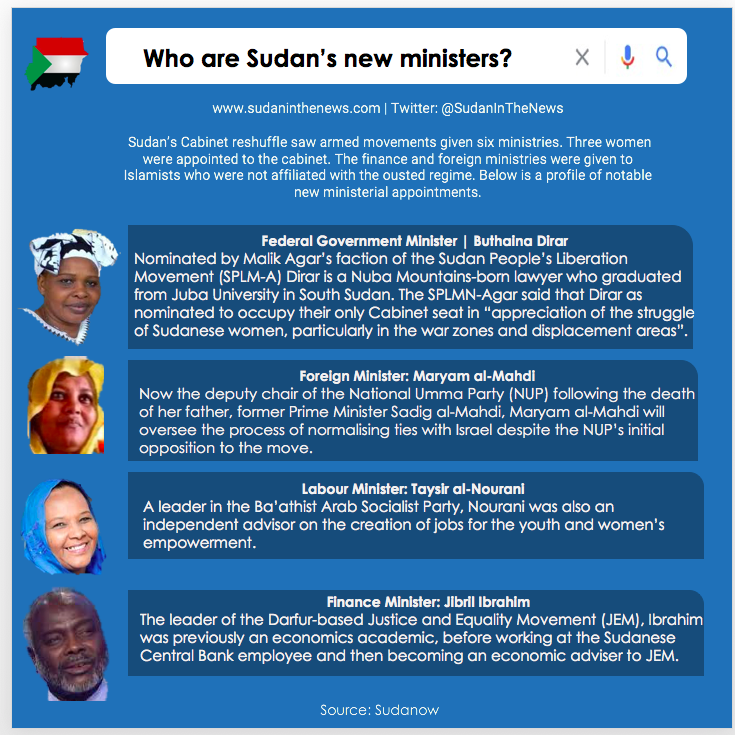

As Resistance Committees are attempt to shape the post-coup political environment, the third challenge is al-Burhan’s re-empowerment of the Islamists that the 2018 uprising sought to remove in his attempts to form a civilian base to legitimise the coup the regime. The re-empowerment of Islamists has enabled them to regroup and retake state institutions, alongside obstructing Sudan’s anti-corruption progress. Consequently, Islamists have a competitive advantage ahead of elections that are likely to be controlled by the military, which poses security risks.

The report concludes with solutions proposed in the Atlantic Council think-tank, US Institute of Peace and Human Rights Watch.

Issue 1: The coup regimes infringement on human rights

In protests that have followed the 25 October military coup, Sudanese security forces have unlawfully detained, disappeared and killed hundreds, with sexual assault being a tool of brutal suppression. In addition, media freedoms are being infringed upon, with journalists covering anti-coup protests being targeted for abuses and the director of Sudan’s national broadcaster being fired for platforming revolutionary voices.

The coup regime’s brutal suppression of the protest movement

In a broad clampdown on opposition to the October 25 military coup, Sudan’s security forces have unlawfully detained hundreds of protesters and forcibly disappeared scores (HRW, 28 April), with Reuters (7 June) reporting that reported that at least 100 Sudanese protesters have died in anti-coup protests. Furthermore, the coup regime is alleged to use sexual assault as a tool of suppression.

The Guardian (16 March) reported that protests took place across in Sudan following the alleged gang-rape of an 18-year-old by up to nine uniformed men belonging to the security forces tasked with dispersing the anti-coup protests. Sulaima Ishaq, the head of the violence against women unit at Sudan’s social development ministry, was quoted to say that security forces are increasingly using sexual assault as a “tactic” to suppress protests, with the security apparatus “using rape as part of their work”. Ishaq added that “it is a well-known oppressive policy in our country … it is not the first time that they have been doing this and it will not be the last time. We have a history of using women’s bodies, whether it is in Darfur or at the dispersal of the sit-in in 2019 or at the protests.”

The coup regime’s crackdown on the media

Furthermore, the coup regime has been infringing on media freedoms in Sudan, with the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor (31 March) recording 55 attacks on journalists by the coup regime from 25 Oct 2021 to 8 March 2022. Security forces violations against journalists and media including: breaking into and closing press offices and institutions, harassment and arbitrary detention and physical and psychological attacks. Euro-Med Monitor identified obstacles to independent journalism in Sudan, including emergency laws and articles of the Penal Code that censor the media and intimidate journalists and activists, with coverage of events that followed the coup and the human rights violations against protesters “considered red lines”.

Indeed, Brig. Gen. al-Tahir Abu Haja, the media advisor to Lt. Gen. Abdulfattah al-Burhan, the commander-in-chief of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), and the chairman of the military-led ruling Sovereign Council, confirmed that the military activated a series of measures to censure and control the media (Sudan Tribune, 15 April). This has included the replacement of state-media directors.

The director of Sudan’s Radio and TV Corporation Luqman Ahmed was fired, with Sudan Tribune (11 April) sources alleging that Luqman’s sacking was triggered by his rejection of attempts by the Military Media Department to intervene in the management of the corporation and its programmes. This was confirmed by al-Burhan’s media advisor Abu Haja, who said that Luqman was dismissed as he “ignored” the news of al-Burhan and the army and broadcast it at the end of the news bulletin (Sudan Tribune, 12 April). Furthermore, Sudan Tribune (11 April) sources also allege that Luqman was sacked due to his invitation of representatives of the Resistance Committees in a talk show he presents, which suggests the ruling military junta has a particular disregard for Resistance Committees being given a platform.

Issue 2: Obstacles facing the pro-democracy movement

The silencing of the Resistance Committees by the coup authorities and the media it dominates has been indicated in the banned broadcast of a talk show discussing the prospects for solutions to the current political strife entitled “From The Revolution Onwards”. Nonetheless, the Resistance Committees - who have become the centre of revolutionary mobilisation - circumvent their exclusion from the state media by issuing charters directly on social media. However, their decentralised nature has led to debate on whether they can implement a transitional roadmap. In addition, the mistrust between the Resistance Committees and the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) coalition of civilian political parties reflect divisions within the pro-democracy movement that enable the military.

Exclusion from the state-media

Samah Mubarak Khater, the presenter of “From The Revolution Onwards” said that decision to ban the show was taken after a complaint by an unnamed army brigadier general – possibly Abu Haja himself - about statements made by a member of the Resistance Committees rejecting the participation of the military in any future transitional government. Khater said the general condemned previous episodes, despite the invitation of army spokesman and a strategic expert to discuss the army’s visions and plans in the next stage (Sudan Tribune, 15 April).

Nonetheless, despite being excluded from the state media, the Resistance Committees are continuing to shape the post-coup political landscape, and assuming leadership of the revolution, through political charters published on social media platforms.

Debates on whether the resistance committees can implement a transitional roadmap

The resistance committees have become the centre of revolutionary mobilisation amid the divisions within the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) and Sudan Professionals Association (SPA), note Marija Marovic, senior advisor to Gisa Group and Zahra Hayder, a Sudanese political activist (USIP, 3 May). However, despite “sustaining the revolution’s energies and combating political apathy,” Marovic and Hayder argue that the decentralised nature of the committees prevents them from participation in national-level political negotiations and coordinating or implementing a transitional roadmap.

On the other hand, Muzan Alneel, cofounder of the ISTiNAD think-tank, reviewed two Resistance Committee (RC) charters that offer a roadmap - the Revolutionary Charter for People’s Power (RCPP) and the Charter for the Establishment of the People’s Authority (CEPA). RCPP analysed Sudan’s historic underdevelopment and proposed that grassroots-led government comprising of local councils focuses on national development projects that transform Sudan from rentier economy to industrialised. CEPA is similar but favours a centralised approach to governance, thereby reflecting revolutionary debate among Sudanese (Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, 26 April).

Furthermore, the centralised approach proposed by CEPA address doubts that the decentralised nature of the committees will prevent them from coordinating and implementing a transitional roadmap. Nonetheless, Islamists attempts to shape the post-coup political landscape face a key challenge – the re-empowerment of the Islamists that came to power in 1989 coup and governed Sudan for 30 yeas.

Civilian divisions enable the military

Nonetheless, according to Kholood Khair, managing partner at Insight Strategy Partners think-tank, the mistrust between the committees and the FFC is argued to enable Sudan’s military, which has historically exploited civilian divisions in order to justify coup staged under the guise of stability. However, Khair argues, while the resistance committees and FFC differ on how to achieve civilian rule, they are united in opposition to a power-sharing arrangement with the military, with political parties that have “historically [agreed]” to sharing power with the military now viewing such a move “as tantamount to political suicide” (Arab Center DC, 22 February).

With the FFC unwilling to provide al-Burhan with a civilian base, the coup regime has instead turned to re-empowering the Islamists that the revolution sought to depose.

Issue 3: the return of the Islamists

After failing to create a civilian base to legitimise the coup regime, al-Burhan is rehabilitating the Islamists ousted in the 2018 uprising. After freeing from prison key leaders of the Islamist National Congress Party (NCP) that governed Sudan before al-Bashir was ousted in a palace coup, Islamists have re-group and formed a coalition. The re-empowerment of the Islamists has been aided by the reversal of a court decision to dissolve the financing arm of al-Bashir’s regime. Moreover, NCP Islamists are being reintegrated into key state institutions, enabling them to conduct a politically motivated campaign against an anti-corruption committee that aimed to retrieve their illicitly gained assets during the pre-coup transitional period. The re-empowerment of the Islamists poses the risk of their victory in controlled elections, alongside the exacerbation of Sudan’s security situation.

How Islamists solve al-Burhan’s problems

According to political analyst Jihad Mashamoun, al-Burhan aimed to compensate for the loss of international legitimacy caused by the resignation of Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok in order to satisfy western warnings against unilateral military appointments of a civilian government (FFC) (Responsible Statecraft, 31 January).

However, al-Burhan’s inability to create a civilian base to form a government indicates that the October 2021 coup leaders have “no political plan other than survival”, argues World Peace Foundation executive director Alex de Waal (Responsible Statecraft, 4 May).

Indeed, after al-Burhan proved to be unable to woo the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) or build a front of non-Communist resistance committees, his failure to appoint a civilian prime minister or build a civilian base forced the Sudanese coup regime to “fall back on Islamists of all stripes” to shore up the regime (Africa Confidential, 12 May). Consequently, the coup regime is “unofficially” rehabilitating the former ruling Islamist National Congress Party (NCP), despite the party remaining formally outlawed, as Burhan’s seeks to “assemble a civilian political base in an attempt to build a case for badly-needed foreign financial support suspended after the coup” (Reuters, 22 April).

NCP leaders freed from prison

Ibrahim Ghandour, the jailed head of the NCP was freed from prison, becoming the most senior figure from the deposed regime of Omar al-Bashir to have charges of crimes against the state dropped since the October 2021 coup. Ex-foreign minister Ghandour was found innocent of undermining the constitution, financing terrorism, and plotting the assassination of former Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok along with other attacks. Two other NCP leaders, Anas Omer and Kamaleldin Ibrahim, were among 12 others cleared of the same charges (Reuters, 7 April).

Radio Dabanga (8 April) added that Ghandour and his co-conspirators were accused of planning to assassinate leaders in the transitional government, bombing the Legislative Council and other government headquarters, as well as planning a military coup, with the charges dropped after the witness retracted his statement under intimidation.

Ghandour then voiced his support for the October 25 coup, saying that it was not a coup, and that it was a “step in the corrective path”, although he argued that al-Burhan “made a mistake” when he signed an agreement on transitional arrangements excluding the NCP, which he stressed, will challenge by all legal means the decision that dissolved and prohibited it. “No one can block our freedom of association,” Ghandour said (Sudan Tribune, 9 April). Nonetheless, the legal status of the NCP has not prevented the formation of an Islamist coalition.

The Islamists regroup

While the NCP remains formally banned, 10 Islamist political groups announced the formation of a new political coalition under the name of “The Broad Islamic Current”.

Among the signatories are the Islamic Movement, a “façade” of the NCP, and the State of Law and Development Party of Mohamed Ali al-Jizouli, “an ISIS supporter released recently from prison”. The coalition aims to coordinate the efforts of the Islamist groups elections, with Islamists seeking to take advantage of the post-coup political environment (Sudan Tribune, 19 April).

Then, a Sudanese high court took “a further step towards the rehabilitation of allies of the former regime” by reversing a decision dissolving the Islamic Call Organization, an organising and financing arm for the regime that has helped to finance Islamist groups (Reuters, 29 April). To further aid the re-empowerment of the Islamists, they are beginning to regain their control over Sudanese state institutions.

The re-empowerment of the Islamists in state institutions

Scores of NCP Islamists have been reinstated into institutions including: the central bank, judiciary, public prosecutor, prime minister's office, foreign ministry and state media (Reuters, 22 April), alongside Sudan’s intelligence agency (Al-Monitor, 19 April). 102 diplomats, including 48 ambassadors, 35 junior diplomats, and 19 administrative staff who are part of the NCP, have also been reinstated (Africa Confidential, 12 May).

In addition, Islamists are using the justice system to free their allies and reverse the seizures of bank accounts and other assets by the Empowerment Removal Committee (ERC) (Reuters, 29 April).

The politically motivated Islamist campaign against anti-corruption efforts

The ERC is a now-suspended anti-corruption body that aimed to dismantle al-Bashir’s deep state (Radio Dabanga, 10 February). ERC was named such as such because the term ‘empowerment’ was used by al-Bashir’s regime to support its affiliates by granting them far-going privileges, including government functions, the setting-up of various companies, and tax exemptions (Radio Dabanga, 28 April).

With Islamists intimidating the ERC’s members (Africa Confidential, 12 May), Sidgi Kaballo, a leader in Sudan's Communist Party, noted that the appointment of Islamists into state institutions, banks and the judiciary is the effective “re-empowerment” that the ERC sought to dismantle (Radio Dabanga, 11 February).

According to Orwa al-Sadig, a member of the suspended ERC who fled Sudan, the committee had revealed operations through Port Sudan airport linked to the Russian Wagner group, fought the drug mafia, stopped land grabbing, and corruption in the sale of the state-owned companies,” and compiled corruption cases threatening the interests of powerful senior officials linked to al-Bashir including ministers and bank directors “who allied to overthrow the [civilian] government” (Sudan Tribune, 21 March).

As a result, the coup regime has been leading a campaign of arrests of ERC members, which the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA) condemned, alleging that they were an effort by the coup authorities to defame the committee’s actions with criminal cases, cancel the committee’s progress in recouping assets and conceal the return of al-Bashir’s Islamist regime (Radio Dabanga, 10 February).

Sudanese lawyers questioned the legal validity of the ‘breach of trust’ cases against the leaders of the now-suspended ERC were launched by the Ministry of Finance, after the ERC instructed the removal of dozens of employees alleged to hold ties to al-Bashir’s regime (Radio Dabanga, 11 February). Committee members were also accused of embezzling public funds, charges they deny as the properties and companies they confiscated are managed by security and ministry of finance officials (Sudan Tribune, 21 March).

While the coup authorities eventually released the arrested ERC leaders on bail (Radio Dabanga, 28 April), exiled ex-member Orwa al-Sadig alleged that the military aimed to use the detained ERC members hostage as a bargaining chip to force them to accept a political settlement (Sudan Tribune, 21 March).

The risk of Islamists winning controlled elections

With Atlantic Council senior fellow Cameron Hudson warning that Sudan’s military leaders are aiming to establish a Security and Defence Council that paves the way for quick elections that provide surface-level legitimacy for the military (Atlantic Council, 11 April), policy analyst Hamid Khalafallah told Al-Monitor (19 April) that, while the NCP remains formally outlawed, the military will “find a way” to allow it to participate in elections if “not with the original name. This risk is emphasised given the formation of an Islamist coalition to prepare them for elections (Sudan Tribune, 19 April).

Security risks of Islamist re-empowerment

The rehabilitation of the Islamists also poses various security risks. Firstly, Suliman Baldo, the director of the Sudan Transparency and Policy Tracker, warned that “bringing back the Islamists could stoke political tension and has already contributed to bureaucratic paralysis” (Reuters, 22 April).

Secondly, Yasir Arman, a leading member of the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC) and the armed Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) warned that the NCP is seeking to exploit the isolation experienced by the coup leaders to control the army again, with the return of the NCP “meaning the return of wars, repression and looting of resources” (Sudan Tribune, 10 April).

In addition, the intimidation of a witness in a trial in which NCP were charged with terrorism indicate that the Islamists in Sudan continue to use violence as a political tool (Radio Dabanga, 8 April).

Finally, the rehabilitation of Islamists and influence over the army may also fuel friction within the security apparatus, amid tensions between Rapid Support Forces (RSF) militia and Islamists who are hostile towards the RSF and feed discontents into the army over the RSF’s growing influence (Sudan Tribune, 6 May).

Solutions

Solutions for Sudan’s post-coup crisis have been directed at the international community and the Resistance Committees.

Recognition that a new transition is being sought

To soften Sudan’s political impasse, Kholood Khair, managing partner at Insight Strategy Partners think-tank, calls for recognition that the transition that started in August 2019 is over, and that a new transition toward a fresh civilian political dispensation is sought. Amid Sudan’s economic crisis, Khair calls for recognition that pro-democracy forces can far outlast the military “who rely so heavily” on economic control. Although divisions within the pro-democracy movement enable the military, Khair adds that key divisions about governance modalities can be negotiated and managed, given that political contestations and ideological differences are “part and parcel of the democratic prerogative that underpins healthy democracies” (Arab Center, 22 February).

Improved public messaging

Atlantic Council (11 April) senior fellow Cameron Hudson calls for the international community adapt its public messaging according to Sudanese public demands and sentiments. This would entail ending calls for the military to enact “confidence-building measures” as this “only plays into the existing discriminatory power dynamics in the country and elevate the security services as an equal, if not legitimate, part of Sudan’s political future”, with calls for “return to civilian-led transitional government…reflecting deafness to popular calls for a new way forward”. Instead, Hudson suggests that the military is reminded that “a return to the pre-revolution status quo is both impossible and unacceptable.”

Unified post-coup leadership body

Marija Marovic, senior advisor to Gisa Group and Zahra Hayder, a Sudanese political activist, argue that the resistance committees (RC) could evolve into forming a unified leadership body for post-coup transitional negotiations as “mass mobilisation against the coup is necessary but insufficient in the absence of unified leadership with clear political demands” (USIP, 3 May).

Addressing deteriorating human rights

Human Rights Watch (28 April) call on Sudan’s international and regional partners and the UN to:

Press the military to lift the state of emergency, allow access for independent monitors to all detention facilities, and stop abusing protesters;

Adopt targeted measures against leaders and commanders of security forces involved in unlawful detentions and enforced disappearances, including those in leadership positions of the Criminal Investigation Directorate (CID) and General Intelligence Service (GIS);

Provide ongoing support to the mandate of the UN independent expert on Sudan and call for invitations for relevant UN and ACHPR experts to visit Sudan; and

Support local groups in their human rights documentation work.